Get analysis, insight & opinions from the world's top marketers.

Sign up to our newsletter.

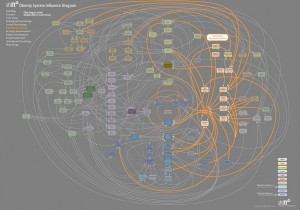

In the UK, back in 2006, a study run by Foresight, a think tank, and commissioned by the then Labour government, found that exposure to food marketing was found to be one of no less than 106 different variables.

This is in no way meant to absolve food marketers of their responsibilities. If food marketing impacts children’s food choices at any level then responsible food companies need to change tack and do something about it.

A responsible industry should take action to limit the marketing on children of products high in fat, salt and sugar. The good news is that many of the major food and beverage manufacturers are already going a long way to doing this.

Last year, the biggest multinationals, which form the International Food and Beverage Alliance (www.ifballiance.org) wrote to the head of the World Health Organisation to make a series of new commitments on labelling, product reformulation and innovation and, notably, a reinforced commitment not to market food and drinks that do not meet strict nutrition criteria to children under the age of 12.

This strengthened policy applies in all markets worldwide in which these companies operate, from China to Chile. Furthermore, they form the basis of local “pledge programmes” in more than 50 countries whereby local and regional manufacturers agree to the same commitments.

In the UK, back in 2006, a study run by Foresight, a think tank, and commissioned by the then Labour government, found that exposure to food marketing was found to be one of no less than 106 different variables.

This is in no way meant to absolve food marketers of their responsibilities. If food marketing impacts children’s food choices at any level then responsible food companies need to change tack and do something about it.

A responsible industry should take action to limit the marketing on children of products high in fat, salt and sugar. The good news is that many of the major food and beverage manufacturers are already going a long way to doing this.

Last year, the biggest multinationals, which form the International Food and Beverage Alliance (www.ifballiance.org) wrote to the head of the World Health Organisation to make a series of new commitments on labelling, product reformulation and innovation and, notably, a reinforced commitment not to market food and drinks that do not meet strict nutrition criteria to children under the age of 12.

This strengthened policy applies in all markets worldwide in which these companies operate, from China to Chile. Furthermore, they form the basis of local “pledge programmes” in more than 50 countries whereby local and regional manufacturers agree to the same commitments.

In Europe, the EU Pledge (www.eu-pledge.eu), a voluntary initiative taken by more than 20 food companies representing approximately 85% of European food marketing spend before the European Commission has resulted in significant outcomes. Since 2005, independent data shows that, on average, children are exposed to 83% less high fat, salt and sugar foods around children’s programmes, 48% less across all programmes and 32% less ads for all company products, irrespective of the products’ nutritional value.

The monitoring is overseen by an independent academic who specialises in children’s safety online. The programme has been welcomed by two successive European Health Commissioners.

Similar approaches are being developed elsewhere. The Singaporean Ministry of Health asked the Advertising Standards Authority to develop self-regulatory guidelines for food advertising to children. The result was a collaboration between industry and the Health Promotion Board, which is part of the Ministry of Health and the Consumers Association of Singapore also had a full say in the process.

Today hybrid, co-regulatory processes are being developed all over the world in countries as diverse as France, UK, Malaysia, the Netherlands, New Zealand, South Africa and Poland, all designed to minimise the impact of food marketing on childhood obesity levels.

Our experience tells us that these schemes work best when they include three elements:

First, any solution needs to be multi-stakeholder and take on board the interests of a variety of parties.

Second, they must employ credible monitoring and enforcement mechanisms.

Finally, and most importantly, the focus must be on outcomes; there needs to be a measureable reduction in the number of ads kids see for certain types of product.

Schemes that meet these three criteria will deliver the desired goals. The ideological debate between regulation and self-regulation becomes irrelevant.

There is no one-size fits all solution given different media markets and the different ways children view media around the world and that’s why a blend of regulatory, self-regulatory and innovative co-regulatory options is key to rapid action that delivers results.

In Europe, the EU Pledge (www.eu-pledge.eu), a voluntary initiative taken by more than 20 food companies representing approximately 85% of European food marketing spend before the European Commission has resulted in significant outcomes. Since 2005, independent data shows that, on average, children are exposed to 83% less high fat, salt and sugar foods around children’s programmes, 48% less across all programmes and 32% less ads for all company products, irrespective of the products’ nutritional value.

The monitoring is overseen by an independent academic who specialises in children’s safety online. The programme has been welcomed by two successive European Health Commissioners.

Similar approaches are being developed elsewhere. The Singaporean Ministry of Health asked the Advertising Standards Authority to develop self-regulatory guidelines for food advertising to children. The result was a collaboration between industry and the Health Promotion Board, which is part of the Ministry of Health and the Consumers Association of Singapore also had a full say in the process.

Today hybrid, co-regulatory processes are being developed all over the world in countries as diverse as France, UK, Malaysia, the Netherlands, New Zealand, South Africa and Poland, all designed to minimise the impact of food marketing on childhood obesity levels.

Our experience tells us that these schemes work best when they include three elements:

First, any solution needs to be multi-stakeholder and take on board the interests of a variety of parties.

Second, they must employ credible monitoring and enforcement mechanisms.

Finally, and most importantly, the focus must be on outcomes; there needs to be a measureable reduction in the number of ads kids see for certain types of product.

Schemes that meet these three criteria will deliver the desired goals. The ideological debate between regulation and self-regulation becomes irrelevant.

There is no one-size fits all solution given different media markets and the different ways children view media around the world and that’s why a blend of regulatory, self-regulatory and innovative co-regulatory options is key to rapid action that delivers results.

For more information or questions, please contact Alexandre Boyer at a.boyer@wfanet.org